Le Corbusier was not just an architect — he was a revolution.

A thinker, a designer, and a provocateur, he reshaped the 20th century with a bold new idea: that architecture should serve the modern human being and express the rhythm of the machine age.

From the elegant minimalism of Villa Savoye to the spiritual power of Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Le Corbusier’s work continues to inspire architects, artists, and urban planners around the world.

Early Life and Origins of a Modernist Mind

Le Corbusier was born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret in 1887 in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. Raised in a family of watchmakers and musicians, he was surrounded by precision, craftsmanship, and structure — qualities that would later define his architectural language.

After studying decorative arts, he travelled across Europe, learning from masters like Auguste Perret in Paris and Peter Behrens in Berlin. These experiences exposed him to reinforced concrete, industrial aesthetics, and new construction techniques — the seeds of modernism.

In 1920, he adopted the name Le Corbusier (derived from a family ancestor) and began publishing essays that would shape the architectural world for decades. His ideas weren’t just about buildings — they were about how people should live in the modern world.

“A House Is a Machine for Living In”

This famous quote by Le Corbusier captures his belief that houses should be designed like efficient machines — functional, clean, and purposeful. He rejected ornamentation and embraced rational simplicity.

He introduced his Five Points of Architecture, the foundation of modern design:

- Pilotis – columns lifting the structure off the ground

- Flat roof terrace – for gardens and open air

- Open floor plan – free of structural walls

- Horizontal windows – to bring in light and air

- Free façade – independent from the structural frame

These principles became the DNA of modernist architecture.

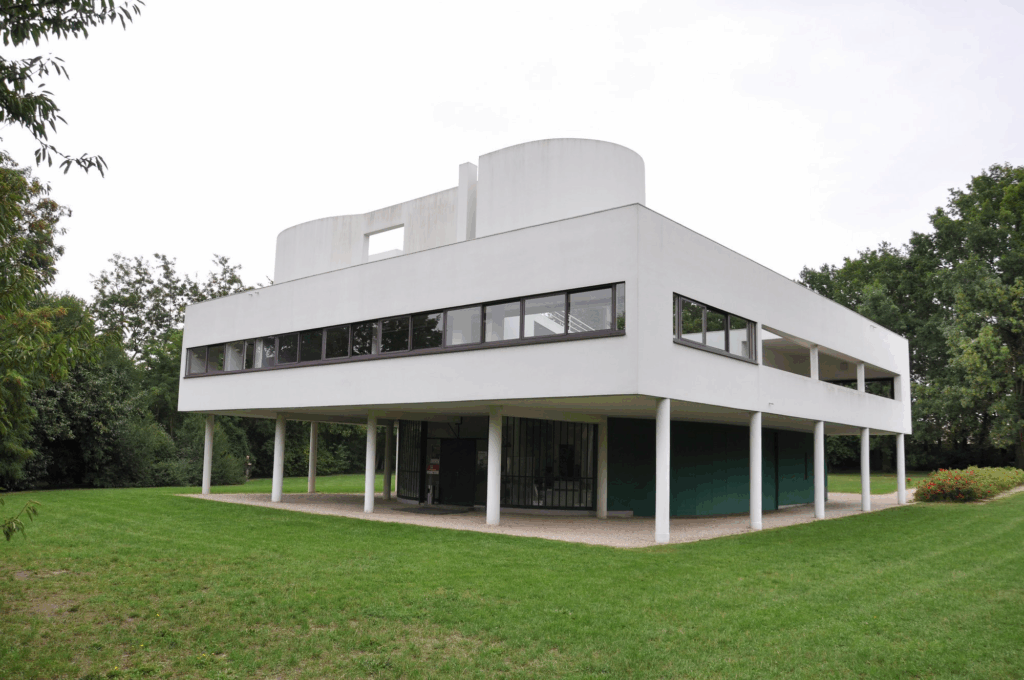

Villa Savoye: The Birth of Modern Living

Completed in 1931 in Poissy, France, Villa Savoye is Le Corbusier’s masterpiece and a textbook example of his Five Points.

The house stands on slender pilotis, its white form floating gracefully above the landscape. The walls are free, the interiors open, and light floods through ribbon windows that stretch across every side.

More than a house, Villa Savoye was a statement — a manifesto of how architecture could embody the speed, hygiene, and freedom of the 20th century. It remains one of the most studied and photographed buildings in the world.

(Image idea: Villa Savoye – “A machine for living in: geometry meets grace.”)

The Unité d’Habitation: Reimagining the Modern City

After World War II, Le Corbusier turned his attention to the problems of housing and urban density. His solution was radical: the Unité d’Habitation — a vertical “city within a city.”

Built in Marseille in 1952, the Unité housed more than 1,600 residents, complete with shops, a school, and a rooftop terrace. Each apartment was designed like a self-contained unit, reflecting his Modulor system — a scale of proportion based on human anatomy and the golden ratio.

This concrete giant, once controversial, became a prototype for modern apartment blocks around the world. Its influence can be seen in everything from post-war housing projects to today’s co-living designs.

(Image idea: Unité d’Habitation – “Le Corbusier’s bold experiment in social housing.”)

Notre-Dame-du-Haut: A Spiritual Revolution

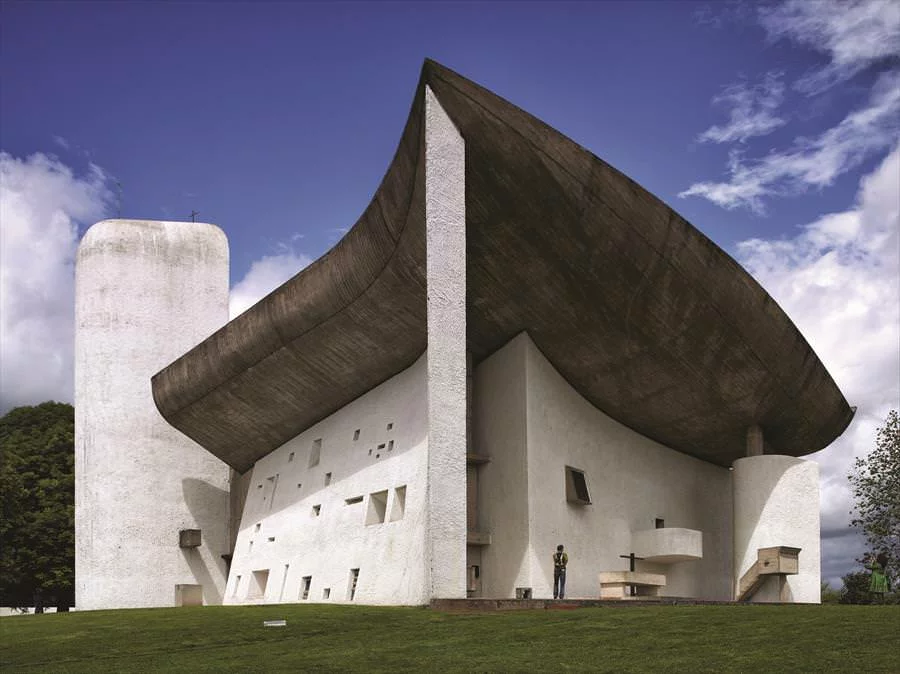

In the 1950s, Le Corbusier’s style took a more sculptural turn. His most poetic creation, the Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut in Ronchamp, France, broke every rule he had previously written.

The thick, curving walls and sweeping concrete roof create a deeply spiritual space filled with silence and light. The tiny, irregular windows scatter beams of color across the white walls, turning the chapel into a living sculpture.

Here, Le Corbusier proved that modernism could have a soul — that concrete could evoke emotion as powerfully as stone or glass.

(Image idea: Ronchamp – “A chapel of light, shadow, and silence.”)

Chandigarh: Designing a Modern Nation

In the 1950s, Le Corbusier was invited to design the new capital of Chandigarh, India. It was his largest project — a city built from scratch, meant to embody progress and democracy.

He designed the Capitol Complex, including the Palace of Assembly, the High Court, and the Secretariat, all built with massive concrete forms and bold sculptural shapes. Chandigarh remains a living example of his urban planning principles — rational grids, open green spaces, and monumental civic structures.

For India, it was a symbol of independence; for architecture, a symbol of ambition.

(Image idea: Chandigarh Capitol Complex – “Where architecture meets governance.”)

Legacy and Lasting Influence

Le Corbusier died in 1965, but his ideas continue to shape the skylines of cities across the world. In 2016, 17 of his buildings were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, recognizing their universal cultural importance.

His influence extends far beyond architecture. His design philosophy inspired generations of urban planners, industrial designers, and artists who sought clarity, proportion, and purpose in their work.

Whether it’s the minimalist apartment you live in or the glass-and-concrete skyline of your city, traces of Le Corbusier are everywhere.

Why Le Corbusier Still Matters Today

In an age of ecological challenges and rapid urbanization, Le Corbusier’s vision feels more relevant than ever. His call for light, air, and space anticipated today’s emphasis on sustainability and human-centered design.

He taught us that architecture is not about decoration — it’s about improving life. His ideas remind us that good design is timeless when it serves people with intelligence, clarity, and beauty.

More than fifty years after his death, Le Corbusier continues to ask us a vital question:

How should we live in the modern world?